‘Glengarry Glen Ross’ Turns 25: Every Performance, Ranked

In 1982 David Mamet wrote Glengarry Glen Ross, a play about salesmen based on his own experiences as an office manager for a shady Chicago real estate company in the 1970s. The 1992 film adaptation, directed by James Foley, didn’t make much of an impression on audiences when it was released. But since then, the film has amassed a much broader following, with numerous lines of dialogue entering the public lexicon. Perhaps watching this ultra-claustrophobic story set inside small rooms with bad lighting and rain-streaked windows is better suited for home-viewing.

The film grossed a little over $10 million, not much when you consider the powerhouse talent assembled in its cast: Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alec Baldwin, Ed Harris, Kevin Spacey, Alan Arkin and Jonathan Pryce. In honor of Glengarry Glen Ross’s 25th anniversary, let’s celebrate its staggeringly talented cast by pitting them against each other to see who comes out on top, much as the characters they play do for an hour and forty minutes onscreen.

A brief note about methodology before we begin: These (100 percent subjective) rankings are based on the quality of the actors’ performances, not the quality of the roles as written. And if we’re being fully honest here, you could probably throw all seven names in a hat, pull them out one at a time, and re-order the list accordingly. But what fun would that be?

So PUT THAT COFFEE DOWN (see number 4, below) and settle in, as we take a deep dive into one of the best ensemble casts in film history. And we must warn you: Just about every one of the clips we’ve embedded below is studded with all manner of profanity, so if you’re at work, PUT THOSE HEADPHONES ON.

7. Jonathan Pryce

During the opening credits, seven names appear before the title of the movie. Jonathan Pryce, who plays the sad, hapless James Lingk, appears last and, in this case, that is deserved. Pryce’s performance is clearly the weakest of those seven. And it’s a marvelous performance, the kind of work that in almost any other movie would send critics into full-on swoon mode, work that, taken on its own, is nuanced, touching and compelling. But in Glengarry Glen Ross, it brings up the rear.

During the process of putting together this list, of re-watching the movie multiple times, only two slot positions never changed. One was Pryce’s at number 7. (We’ll get to the other one a bit later.) The role of James Lingk is a small but crucial one. His part in the story is, basically, a mark — superstar salesman Ricky Roma gets him drunk at a bar and gives him a smooth-talking spiel about, you know, life, man, right? (You can watch that speech a little lower on this list.) Within a few hours, Lingk has given Roma a five-figure check for some garbage land in Florida called the Glengarry Highlands that he’s never even seen and knows nothing about.

In Pryce’s first of two scenes as Lingk, when Roma seduces him, we know nothing about him, only that he’s a middle-aged guy sitting in some dingy bar, drinking scotch with a stranger. He does seem to really like how Roma flatters him, flirts with him, tells him how the world could be his if just reached out and grabbed it. Lingk smiles all the way through, clearly enjoying himself even as he has no idea what’s actually happening:

The next morning we meet a very different James Lingk. He shows up at the real estate office to ask Roma for his money back. He’s on the edge of complete collapse here, and it’s tough to watch a man grovel like this. When he tells Roma “I don’t have the power,” he can barely get the words out. Whatever is going in Lingk’s home life — A disintegrating marriage? A long-repressed sexual orientation? — he can hardly contain his pain anymore. He’s on the verge of something terrible. It’s the mark of a great performance, that even though we only meet him briefly, we’re curious about just what this guy’s deal is — couldn’t we have a movie about him?

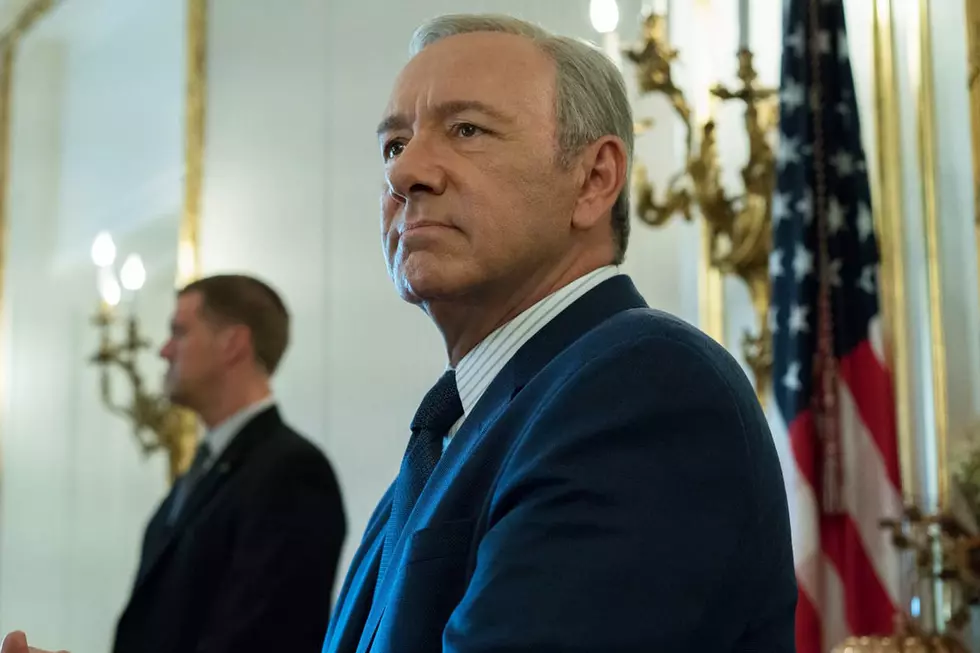

6. Kevin Spacey

The sixth-best performance in most movies would normally be an afterthought, but the acting in Glengarry is so strong and so deep, it’s sort of like being the sixth-best Beatles album, or the sixth-best player on the Dream Team — you’re a first-ballot Hall of Famer, but you can’t even crack the starting lineup on your own squad.

For Kevin Spacey, this was a career breakthrough, performing onscreen with some established Hollywood heavyweights and holding his own throughout. His famous “Will you go to lunch!” speech is a perfect example of what people mean when they talk about the music and rhythm in David Mamet’s dialogue — and in this case, how an actor can discover and use it. Listen to how each word fires out from Spacey’s mouth:

Now will you go to lunch?

(beat)

Go to lunch.

(beat)

WILL you GO to LUNCH!

Late in the film, when Williamson figures out that Shelley robbed the office, it’s a delicious moment — for both the character and, clearly, the actor. Finally, after a whole movie’s worth of abuse at the hands of the men he’s ostensibly managing, he gets to spit some venom back. When Williamson explains that Shelley's sale to the Nyborgs isn't going to go through, he enjoys watching Shelley’s face and, really, whole life crumble. “They just like talking ... to salesmen.” It’s a line (at about 3:35 below) that feels like it was written with this one particular actor in mind:

Remember, Mamet was the office manager at his real estate firm, making Spacey’s John Williamson the Mamet stand-in, a fun tidbit of trivia.

5. Al Pacino

Yes, for the record, it feels weird to say that Jonathan Pryce, Kevin Spacey and Al Pacino gave the worst performances in any single movie, but hey, here we are. Pacino is the only one who received any Oscar attention for Glengarry Glen Ross, as he nabbed a Best Supporting Actor nomination (he lost to Unforgiven’s Gene Hackman). But don’t feel bad for Al; he took home Best Actor that year for Scent of a Woman.

Which in some ways is a shame, because his work in Glengarry is far superior. Gone are the bombastic whoops and wide-eyed, ostentatious displays of ACTING!!! that apparently Academy voters drank up. And sure, Pacino does get to do a bit of yelling and swearing here (it is a Mamet movie), but it’s his restrained moments that make everything else work. Roma is the top salesman at Premiere Properties, and the one time we watch him make a sale, he barely even mentions real estate — and even then, it’s only at the very end. By the time Roma pulls out the Glengarry Highlands brochure, he’s already made the sale. Lingk would buy anything from this guy. And who wouldn’t? Watch the master at work:

As a side note, the part of Ricky Roma may be a bit more effective in stage productions than in film. Maybe. Joe Mantegna won a Tony for the role in 1984, and Liev Schreiber repeated his success in the 2005 revival. It’s Roma, more than the others, who has live audiences eating out of his hand with all the zingers and put-downs and gleeful profanity. Onscreen, this kind of talking-to-hear-oneself-speak can work in the hands of a genius like Pacino, but seeing it live onstage is a whole other kind of experience. As Mamet said when asked if Roma is more a glass-half-empty or glass-half-full kind of guy, “He’s the kind of guy who’d give you the history of water, starting with the cavemen.” And then we’d buy the water.

4. Alec Baldwin

First prize is a Cadillac Eldorado. Anybody wanna see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired. Do you get the picture?

The most well-known scene — certainly the most frequently quoted — in Glengarry Glen Ross was not in the original stage version, the version that won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1984. So why would you mess with a masterpiece like that? Why add a whole new scene with a whole new character to something that’s already so great and complete?

Because of that quote above. This scene, right at the start, sets the stakes for the men of Premiere Properties. Four salesmen work there, and at the end of the month, half will be fired. Each man’s desperation to make a sale that night, to repeatedly phone up customers who obviously don’t want to buy anything, to go so far as to to plot a burglary of their own office, it all stems from this. It’s why everyone is so high-strung all the way through, why they won’t, they can’t, take no for an answer.

Mamet wrote the scene explicitly for Alec Baldwin — in order to pay Baldwin back for welshing on a dinner check years earlier — and Baldwin turned it into an instant classic. He probably didn’t realize that these seven minutes might end up being what best defines his career. Even people who haven’t seen Glengarry know that “Coffee is for closers,” the way they know that Rosebud is a sled without watching Citizen Kane.

“What’s my name? F—

YOU, that’s my name.”

In the closing credits, Baldwin’s character is revealed as “Blake.” However, the name he gives himself, “F— you,” is far more accurate and appropriate.

3. Ed Harris

Dave Moss is generally not considered one of the plum parts in Glengarry Glen Ross (unless you consider all seven to be pretty darn plum, which is reasonable), but Ed Harris turns this working man’s working man into a tornado of anger, deceit, and bitterness, raising him above the other, showier roles.

Perhaps the best sale made in the whole movie is Moss getting Levene to rob the office for him. That’s impressive work; we can understand how Moss got to be second on the sales board. We never actually see how he persuades Levene, though we do get an idea by watching how he masterfully, patiently manipulates Aaronow, who, like Lingk with Roma, has no idea what he’s getting into even as it’s happening.

Later on, Moss gets one of the all-time-great exit speeches, one that could probably only be written by David Mamet and perhaps not played any better than by Ed Harris:

When Siskel and Ebert reviewed the movie in 1992, Gene Siskel said of Harris, “I thought Ed Harris was the most credible salesman of them all.” That feels exactly right.

2. Alan Arkin

What is a man like George Aaronow, as played by Alan Arkin, even doing in this office? He doesn’t fit in with the rest of these sharks. He’s a quiet, nervous type, in stark contrast to F-bomb-spewing alphas around him. He’s the only one who ever expresses any self-doubt, the only one who uses the same voice on the phone with customers as he does with his co-workers. He’s managed a paltry $4,000 in sales this month, and it’s a miracle he made even that much.

All that is why he’s a breath of fresh air. The way Arkin plays him is funny and sad at the same time, a man out of place who seems to know he’s out of place. During Blake’s fiery threats, Aaronow stays silent the whole time, barely lifting his eyes up off the floor, like he’s already accepted his fate of “You’re fired.” When Moss introduces the idea of the robbery, you almost get the sense that Aaronow wishes he would have just up and quit the job earlier, like he can see how things will only get worse from here:

The degree of difficulty in executing intricate dialogue, direction changes, and word repetition like that is off the charts, and Harris and Alan Arkin pull it off beautifully. (Check out pages 52–53 of the shooting script and try to imagine reaching that level of precision.)

(And if you want to see the meek Aaronow finally get fired up, just re-watch his “I mean Gestapo tactics!” meltdown from during the Williamson “Will you go to lunch!” scene above.)

Aaronow also gets one of the film’s final lines and, as seems to happen for each of the spectacular actors in this movie, after hearing it, it’s all but impossible to imagine anyone else saying it. Ladies and gentlemen, here’s Alan Arkin as George Aaronow summing everything up perfectly:

*** Thunderous applause ***

1. Jack Lemmon

After Jonathan Pryce as James Lingk, the only other slot that never changed during the writing of this piece was Jack Lemmon at number 1. His portrayal of Shelley “The Machine” Levene is a captivating picture of a desperate man driven to desperate acts, and all for naught in the end.

During Glengarry Glen Ross’s production, the actors referred to it as “Death of a F—in’ Salesman,” and even though no one literally dies, that’s exactly how it feels at the end, when Levene hesitantly saunters into the office, where the cops await him. His career is dead, that's for sure, and as he told Williamson just a bit earlier, “A man is his job.” It’s the walk of a man who knows that it’s over, that he has no cards left to play, that he finally, at last, cannot talk his way out of this. You can read so much on Levene’s face as he tries, futilely, to say one last thing to his protege, Ricky Roma. But “Ricky can't save you,” the detective says.

The Alec Baldwin scene may hog all the attention, but there’s another scene written just for the film adaptation, and it’s just as good, though for different reasons: when Levene goes to Mr. Spannel’s house. In this scene, we see him try every move in the salesman’s repertoire. You can’t help but feel bad for both men here. Levene knows this guy isn’t gonna buy anything, he doesn’t even want this poor old man in his house. Mr. Spannel knows that Levene knows, and Levene knows that Mr. Spannel knows. It’s uncomfortable, but true. Watch as Levene keeps that smile glued to his face, how he tries to spin every sentence into a personal connection — or what passes for a personal connection in a salesman’s world anyway:

A failed sale capping off a failed career in a failed life. That’s perhaps a harsh way to look at it, but there’s a moment we can contrast it to. The next morning, Levene does make a sale (or at least he thinks so at the time), and his description of it to Roma shows you everything you need to know about what Levene calls “the old days,” back when he was tops on the sales board, when he ruled the office. It’s his final moment of happiness, and even though we find out later that it was hollow all along, that the Nyborgs are insane people who “just like talking ... to salesmen,” this retelling gives us a clue as to what Levene wishes life was like, how it once really was for him.

Without seeing this first, Levene’s final fall from grace wouldn’t land nearly as hard, and Lemmon squeezes the moment for all it’s worth:

You almost want to see a prequel now — call it Glengarry Glen Ross: The Old Days. Trouble is, you’d never be able to find a cast half as good.

More From WKFR